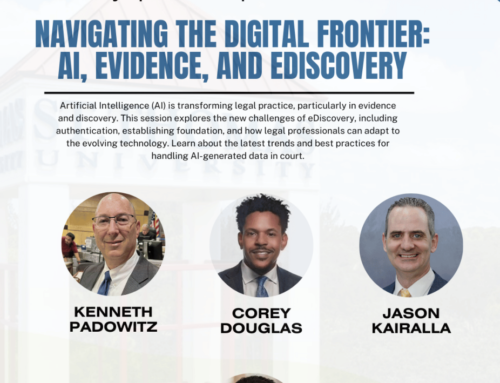

A Fort Lauderdale, Fla., based attorney, Kenneth Padowitz, first used animation technology as the prosecutor in a 1993 trial involving a hit-and-run driver who ran into five children, killing one of them. The eventual guilty verdict was challenged by the defense, but a Florida appellate court sided with Padowitz. It was the first appellate decision in the U.S. upholding computer animation as evidence in a criminal trial.

First Forensic Computer Animation entered into evidence by Trial Lawyer Ken Padowitz, March 8, 1993

CHRISTIAN NOLAN

The Connecticut Law Tribune

10-08-2012

See Related Post by Ken Padowitz on Topic of Animations v. Simulations

For about as long as there have been fatal accidents leading to criminal charges, there have been accident reconstruction experts testifying in court as to what exactly went wrong.

The experts, often members of state police teams brought in by prosecutors, figure out who was at fault by examining skid marks, vehicle damage, or black boxes in cars that contain an array of data, including speed at impact. While all this information may help juries reach their decisions, the fact of the matter is jurors must still use their own imaginations to try to picture exactly what happened.

Those days may be numbered.

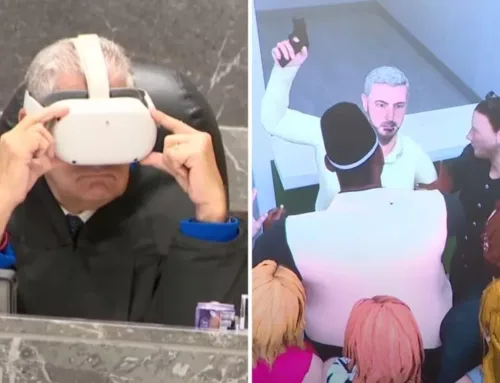

For the first time ever in a Connecticut criminal case, an animated video recreating a crash will be used in a criminal trial. Jason Anderson, a former Milford police officer, is charged with racing in his police cruiser and smashing into a car carrying two teenagers, David Servin and Ashlie Krakowski, in 2009. Both were killed, and the officer, who was allegedly traveling 94 mph without his lights or siren on, is charged with manslaughter.

Anderson’s attorney, Hugh F. Keefe, of Lynch, Traub, Keefe & Errante in New Haven, filed a motion to prevent the computer animation recreation from being introduced. Last month, Keefe told Superior Court Judge Denise Markle that the video would distort the truth and described it as a “Disney World-created fantasy tape.”

Milford-Ansonia State’s Attorney Kevin Lawlor told the judge the video would help the jury understand factors involved in the accident, such as time, speed and space. “People have trouble understanding those types of concepts,” Lawlor said.

Markle ruled last week that some of the animated evidence would be allowed at trial, such as how the accident might have looked from different vantage points around the crash site. Some of the video animation was disallowed, such as hypothetical depictions of what might have happened had the cruiser been traveling at a slower speed.

The judge has not yet ruled on the admissibility of two other videos.

First Decision

A Fort Lauderdale, Fla., based attorney, Kenneth Padowitz, first used animation technology as the prosecutor in a 1993 trial involving a hit-and-run driver who ran into five children, killing one of them. The eventual guilty verdict was challenged by the defense, but a Florida appellate court sided with Padowitz. It was the first appellate decision in the U.S. upholding computer animation as evidence in a criminal trial.

Padowitz is not surprised Judge Markle is allowing it in the Anderson case. “Most states allow this now as an accepted form of evidence in court as long as it meets some basic criteria,” said Padowitz. “By comparison, we allow photographs and movies. This is now an extension of that.”

Padowitz acknowledged that defense lawyers often argue that the animation evidence is prejudicial to their client or they belittle the video as not portraying reality. But, he said, they would be better off utilizing the animation technology themselves to counter the prosecution, especially if they have their own expert with a different version of how an accident happened.

“All evidence, whether brought by the prosecution or defense, is prejudicial, that’s why we’re entering the evidence in,” said Padowitz. “But does the prejudicial effect outweigh the probative value? Courts have been ruling no, video animation is not more prejudicial than probative. It’s just got to be fair and accurate.”

Sgt. William Telford, who heads the Connecticut State Police’s Collision Analysis and Reconstruction Squad, or CARS, said State’s Attorney Lawlor approached him sometime after the Milford officer’s arrest and asked him about the possibility of making an animation of the accident scene. At that point, Telford told the prosecutor that the state’s technology was not up-to-date. “Computer technology that’s seven or eight years old is like 100 years old in computer age,” said Telford.

But Lawlor’s request put some wheels in motion. “We got the authorization through our chain of command. The decision was made that [new] technology would be something that’d be great for our future capabilities for crime scenes and crash scenes,” said Telford. “State’s Attorney Lawlor was the one who happened to push this forward.”

In June, the state police squad received the new technology, called ARAS 360 HD, from a Canadian manufacturer. Telford acknowledged that the animation is comparable to video game graphics. “Some lawyer’s going to jump all over that,” he said, referring to Keefe’s “Disney World” metaphor.

“That’s not really the parallel we want to draw, but that is kind of what it looks like,” said Telford.

He said the software enables officers to accurately depict an accident scene and the area around it, including the sizes of nearby buildings, the configuration of the traffic lanes, etc. “It’s an additional tool for us to look at and examine and see how things may or may not have occurred based on the evidence we locate in the roadway,” said Telford. “It’s amazing what you can do with computers now.”

The animation itself, Telford admitted, is “more for assisting prosecutors.”

“Now [a jury] can see [the crash] and not have to imagine it in their head,’ said Telford. “You’ve got vehicle’s going 70, 80, 90 mph and when they hit each other they do crazy things. The forces at those speeds cause vehicles to do things the mind wouldn’t really normally think could happen.”

“All evidence, whether brought by the prosecution or defense, is prejudicial, that’s why we’re entering the evidence in,” said Padowitz. “But does the prejudicial effect outweigh the probative value? Courts have been ruling no, video animation is not more prejudicial than probative. It’s just got to be fair and accurate.”

Manpower Issues

Telford said it takes a lot of manpower just to do one crash scene animation, so state police will use the technique sparingly. However, he added that the animation approach could also be used to recreate other types of crimes, even murders and robberies.

The sergeant acknowledged that depending on the outcome of the Anderson trial, he may start hearing from more prosecutors in the state.

“We’re down in manpower,” said Telford. “So it’s certainly going to be a strain and a lot of additional work. It’s going to be on a case-by-case situation and need.”

Lawlor told the Law Tribune that it was “a fair assumption” to think the animation may be utilized by more prosecutors depending on the outcome of the Anderson trial. “I would think it would be, if admissible, other prosecutors would take a look at using it,” said Lawlor.

It’s not as if video animation technology is unheard of in Connecticut courtrooms. Litigators have been using it increasingly to recreate accidents in civil trials. In a recent Law Tribune article, personal injury lawyer Carter Mario said the technology puts “the fact finder in the right frame of reference to see and experience what occurred.”

Padowitz, the Florida attorney, agreed the animation videos are still more common in civil cases in which the cost of making them is less of a factor. “Upwards of 90 percent of criminal cases end up pleading out,” he noted. “Many times prosecutors are reluctant to spend money on a visual aid, whereas in civil cases there are thousands to millions [of dollars] at stake, so lawyers are more apt to turn to this technology.”

Keefe, the very same defense lawyer who fought to prevent the animation evidence from being used in the Anderson trial, said he uses similar technology in civil cases. Recently, he used computer animation technology in the Emma Jones v. East Haven trial, in which a woman sued the town after a police officer shot and killed her son, Malik, after a long car chase.

The difference in the civil and criminal cases, said Keefe is “that I had a witness who testified [what is depicted in the animation] is exactly what he observed. In this case, [the prosecution] doesn’t pretend to have that as foundational testimony.”•