“I was a prosecutor for 16 years, and there were many times I thought someone committed perjury, but what I believe and what I can prove with evidence are two different things,” Padowitz said.

The perjury charge that led to Wednesday’s arrest of Broward Public Schools Superintendent Robert Runcie is extremely rare and difficult to prosecute, legal experts said Thursday.

And in the wake of the charge, handed down by a statewide grand jury in an indictment that did not detail specifics, Black leaders in South Florida have pointed to political maneuvering by Gov. Ron DeSantis, who authorized the grand jury in February 2019, a month after he took office.

“We are in support of Superintendent Runcie, and ask that due process is exercised,” said Eric Knowles, founding member of the South Florida Black Prosperity Alliance, a non-profit aimed at supporting Black businesses and political leaders. “We stand by to monitor the allegations and we do not support or believe that they are in the best interest of our community.”

DeSantis’ office did not return an emailed request for comment on Thursday.

The investigation involves the district soliciting and receiving state funds for school safety measures mandated after the Feb. 14, 2018, massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, which led to the deaths of 17 students and faculty members and the wounding of 17 others.

Runcie is accused of making at least one statement to the grand jury between March 31 and April 1 that he knew not to be true, according to the April 15 indictment, which charged him with perjury in an official proceeding, a third-degree felony. The school district’s top attorney, Barbara Myrick, 72, was also indicted, but for unlawful disclosure of statewide grand-jury proceedings.

Both were arrested on Wednesday by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. Both were released on their own recognizance later that morning. They’re both scheduled to be arraigned at 9:30 a.m. May 12 in front of Broward Circuit Judge Martin S. Fein.

PERJURY CHARGE IS ‘QUITE RARE’

Attorney Craig Trocino, director of the Innocence Clinic at the University of Miami School of Law, said he cannot remember the last time he’s read about a perjury charge being brought during a grand jury proceeding.

“Grand jury perjury indictments are quite rare, and, it’s surprising for me to see it in this context,” Trocino said Thursday.

This is because the prosecution has to prove that both the statement was not true and it’s germane to the proceeding, Trocino said.

“This is rare, and it’s strange that it came up this way, and the indictment is so threadbare,” he said.

Trocino said he was only aware of two perjury cases in South Florida, both in Miami-Dade in 2013, and both were dismissed.

The indictment does not say what statement Runcie said during testimony that prosecutors deem not to be true. And, Runcie’s attorneys, Michael Dutko and Jeremy Kroll, said prosecutors still haven’t told them.

“There has been no information provided as to what was purportedly false,” Kroll said Thursday.

Grand jury perjury charges are rarer still because most grand juries are impaneled for capital cases like murder. Most other criminal charges are brought by a county’s State Attorney’s Office.

The grand jury was tasked with investigating whether the Broward School District violated the state school safety laws passed after the Parkland shooting or whether it misused funds from bond money meant for school safety initiatives.

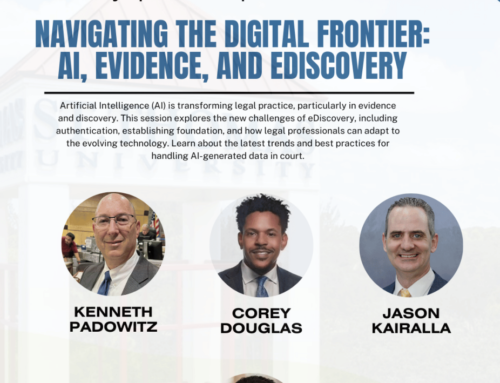

“In the context of it being a government official, that explains why it was an indictment by a grand jury and not an individual prosecutor,” said Ken Padowitz, a criminal defense attorney who worked as a prosecutor for the Broward County State Attorney’s Office for 16 years.

The grand jury was scheduled to finish its work after a year. But, because it could not meet in the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was extended. The grand jury wrapped up on April 17, said Kylie Mason, spokeswoman for Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody. Runcie was indicted on April 15.

Padowitz, like Trocino, said the perjury case against Runcie will likely be difficult for prosecutors to make because they have to prove not only he lied, but that the alleged lie is material to what grand jurors were investigating.

“I was a prosecutor for 16 years, and there were many times I thought someone committed perjury, but what I believe and what I can prove with evidence are two different things,” Padowitz said.

Another reason perjury in grand jury cases is so infrequent is because witnesses are told repeatedly by prosecutors that they face incarceration if they lie under oath, said David Weinstein, an attorney who served 11 years as an assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Florida.

“You’re hardly ever going to see it,” he said.

DEFENDANT HAS RIGHT TO KNOW SPECIFICS BEHIND CHARGE

While indictments normally don’t go into specifics about the alleged crime committed, and the grand jury proceedings are conducted in secret, Weinstein said Runcie’s attorneys at least should know more by now.

“You’re obligated to tell a defendant what it is the lie he or she made,” he said.

On Wednesday, a spokesman for DeSantis did not say whether he would remove Runcie from office in the wake of the indictment. “At this point, this is a matter for law enforcement and the courts,” Cody McCloud, DeSantis’ press secretary, said in a statement.

In January 2019, shortly after taking office, DeSantis told reporters that while he had heard the calls from Parkland families to oust Runcie, he could not do so by law, since the superintendent was hired by the School Board, and was not an elected official. He said there may be other “options” for accountability.

PARKLAND PARENTS BLAME RUNCIE FOR SCHOOL SHOOTING

At least some members of the School Board blame Runcie for the conditions that led up to Nikolas Cruz, a former Parkland student, opening fire on his former classmates. Specifically, Runcie was instrumental in implementing an initiative that placed students who commit certain misdemeanors in an alternative school rather than getting the police involved.

School officials transferred Cruz from Stoneman Douglas in 2017 to an alternative school over disciplinary issues related to fighting, profanity and a Jan. 19, 2017, assault.

Tony Montalto, president of Stand with Parkland and whose 14-year-old daughter Gina was killed in the shooting, praised DeSantis’ actions in a statement issued by the group:

“We are happy that governor DeSantis created the grand jury to investigate the failings of school districts in the state of Florida. The grand jury is doing its job by holding the people who are responsible for the safety of our children and staff members accountable. We know that Mr Runcie’s poor leadership contributed to the Parkland tragedy.“

In 2019, School Board member Lori Alhadeff, whose 14-year-old daughter Alyssa was killed in Parkland, led an unsuccessful effort to have Runcie removed. The motion was rejected in a 6-3 vote.

Alhadeff said in a statement Wednesday that she is waiting for input from the district’s human resources department before giving her opinion on whether Runcie should be removed as a result of the indictment.

“As more specific details come to light, I will act accordingly, in the best interest of the students and staff at BCPS,” she said.

The school district released a statement Thursday saying the school board is scheduled to discuss Runcie’s arrest and indictment at its Tuesday meeting. Broward County Public Schools is the nation’s sixth-largest school district, with approximately 261,000 students.

SUPPORTERS POINT TO RUNCIE’S EDUCATIONAL GAINS

Broward County Commissioner and former Broward mayor Dale V.C. Holness strongly supported Runcie in a statement he issued Thursday night, citing the educational gains made under Runcie, who was hired by the district in 2011. The School Board extended his contract in 2013 and again in October 2017, when it unanimously approved a second extension until June 30, 2023. He earns $356,000 a year.

“Through Superintendent Runcie’s leadership, the graduation rate for all of our students has drastically increased to the highest rate since the Federal Uniform Graduation Rate was adopted in 2011, to 89.4% in 2020. Remarkably, this increase was observed across all ethnicities in our community as the Black, Hispanic and White graduation rates increased to 86.5%, 90% and 92.4%, respectively.”

“… At the start of the decade, the district had over 50 “D” and “F” rated schools, many of which were disproportionately located in less affluent and minority communities. Today, thanks to the leadership of Superintendent Runcie, there are 69 “A” schools, 54 “B” schools and zero traditional schools that received an “F” report.”

Runcie’s attorneys have said politics are at play and their client has fully cooperated with the statewide grand jury process since the beginning.

The indictment of Runcie and Myrick is not the first time the grand jury took legal action against a Broward Schools employee. In January, it indicted Anthony Hunter, 60, the district’s former chief information officer, on charges that he steered a lucrative classroom technology contract to a friend’s business without seeking other bids.

The case against Hunter, who pleaded not guilty, is pending.

Trocino, the UM professor, theorizes the indictment is the last action prosecutors plan to take against Runcie. But, he said the superintendent and his legal team deserve to know more about the allegations.

“The Fifth Amendment has this little thing in it that you’re supposed to know what you’re charged with,” he said.

Miami Herald staff writer Samantha Gross and Miami Herald researcher Monika Leal contributed to this report.

To read the original article on the Miami Herald CLICK HERE