“The burden is very high for the government,” Padowitz said. “Time can provide reasonable doubt to a good defense attorney.”

The clown walked peacefully away from the murder — something Joe Ahrens has never been able to do.

The world slowed for Ahrens the moment his mother, Marlene Warren, opened the front door of their Wellington home on May 26, 1990, and a clown greeted her with two balloons, flowers — and a gun.

He was in a “daze” once he saw his mother lying on the floor, shot in the mouth. Despite the shock, he jumped into his mother’s brand new car and sped after the clown who was fleeing in a white Chrysler LeBaron. Ahrens — running red lights, prepared to crash into the getaway car — was willing to risk his life to catch the person in the disguise.

He made it to Southern Boulevard, 10 miles away. The clown and LeBaron were nowhere to be seen. And while the car would soon be found abandoned in a Winn Dixie parking lot, the killer would remain unidentified for 27 more years.

Paramedics take Marlene Warren, 40, to an ambulance on May 26, 1990, after she was shot at her home in Wellington.

Sheila Keen Warren pleaded guilty last month to second-degree murder in the killing of Ahrens’ 40-year-old mother. Marlene Warren, gunned down in front of her son and a friend, was the wife of the man Keen Warren would later marry.

Keen Warren’s defense attorney estimated she could be free in as few as 16 months because of the time she’s served while awaiting trial, while prosecutors said she will be behind bars for at least another two years.

The start of the trial was less than three weeks away when the plea deal was reached. Everyone was ready. But Judge Scott Suskauer had yet to rule on the sole outstanding motion, and prosecutors “had serious concerns” his decision would not be in their favor, State Attorney Dave Aronberg said.

The unsettled matter was whether fibers and DNA evidence from human hair found in the LeBaron would be allowed at trial. Aronberg said prosecutors were “facing the real possibility” that all of that evidence — what Aronberg considered their strongest — would be excluded.

“It came to the point where we knew we had a good faith basis to proceed to trial, but we also knew that there was a growing chance that we would not be able to meet our high burden of proof,” Aronberg said.

Defense attorney Greg Rosenfeld was ready to attack the fibers and DNA at trial, evidence he said did not show Keen Warren committed the crime or was at the crime scene. He maintains Keen Warren is innocent, but the certainty that she would walk out of prison outweighed the uncertainty of what could happen at trial, he said after the plea.

Ahrens, though, said he is certain that Keen Warren was the clown.

“Today, there’s no doubt that that woman was in that clown outfit,” Ahrens said. “There’s no doubt in my mind.”

Former Broward Chief Assistant State Attorney Chuck Morton, who prosecuted the infamous 1994 Casey’s Nickelodeon triple murders of a bar owner and some friends at multiple trials over a span of 18 years, and Ken Padowitz, former Broward Homicide Unit Assistant State Attorney and now criminal defense attorney, said time more often than not hurts prosecutors’ cases.

‘Undermined by Father Time’

Keen Warren became a prime suspect in the case early on. Marlene Warren’s husband, Michael Warren, owned a used-car business where Keen Warren worked for him repossessing cars. It was rumored in 1990 that the two had an affair. Both denied it initially. They married in 2002.

That time had hindered both the defense and prosecutors in Keen Warren’s case had long been known. Key witnesses are dead, have moved away or were unable to be found. The memories of those still alive continue to wane. Each of the several times the trial’s start date was delayed brought the risk that other witnesses, some elderly and sick, could die.

Former Broward Chief Assistant State Attorney Chuck Morton, who prosecuted the infamous 1994 Casey’s Nickelodeon triple murders of a bar owner and some friends at multiple trials over a span of 18 years, and Ken Padowitz, former Broward Homicide Unit Assistant State Attorney and now criminal defense attorney, said time more often than not hurts prosecutors’ cases.

“The burden is very high for the government,” Padowitz said. “Time can provide reasonable doubt to a good defense attorney.”

Aronberg said a “damaging blow” came with the death of the lead crime scene investigator, Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office Sgt. Michael Free, in 2020. A witness typically needs to testify before jurors how evidence was found and how it had been handled, Aronberg said. Without Free, the fiber evidence could no longer be authenticated.

“Memories fade, but those fibers provided timeless evidence,” Aronberg said. “But with the death of the lead crime scene investigator, we lost our best evidence.”

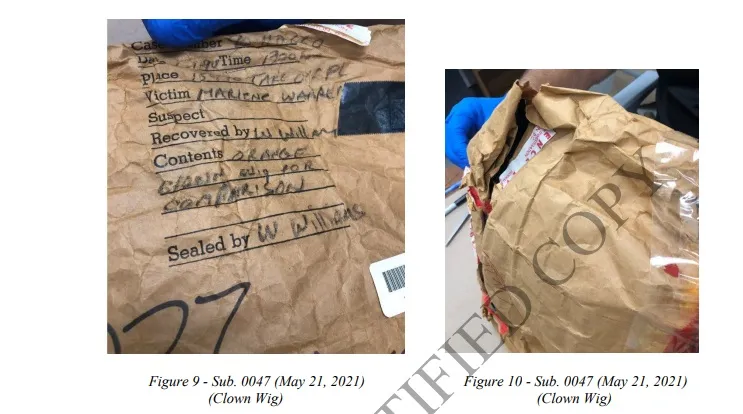

Years after the crime, an orange wig-like fiber had been found on the ribbons of the balloon the clown gave Marlene Warren. Other fibers were found in a 1990 search of Keen Warren’s apartment, including on pairs of shoes at her home. Prosecutors said those fibers matched the fibers from a clown wig detectives purchased from the Spotlight Capezio costume store, which they said in one court filing “was the exact type of wig” Keen Warren bought from the store. Detectives had to buy the wig at the costume shop because the one the killer wore was never found.

Morton, the Broward prosecutor, said with the death of the lead crime scene investigator who could testify to the chain of custody of the fiber evidence in Keen Warren’s case, the state likely lost its ability to convince a jury “of its strength and persuasiveness.”

“The problem they ran into was, where did it originate from? Because if it came from the crime scene initially and it was there all along, then why wasn’t it accounted for all along and couldn’t this case have been solved a lot sooner?” Morton said. “So that was a big problem they had evidentiary wise.”

Sgt. Free also collected fibers and human hair from the LeBaron. DNA testing of one of the hairs showed Keen Warren was the source, prosecutors wrote in one court filing in 2021.

Her defense attorney argued that the various fibers should be excluded from trial because, in part, many of the evidence bags were improperly packaged, opening the door for possible contamination.

“Even for 1990, these practices were unacceptable,” Rosenfeld said. “It’s horrifying.”

Rosenfeld wrote in his Feb. 18 motion that the detective who collected the balloons from Marlene Warren’s home the day she was killed maintained he never saw a small wig-like fiber on the ribbons. It wasn’t found until 2014. Rosenfeld wrote that the wig-like fiber on the ribbons could have come from another evidence bag that was also open — the bag containing the clown wig that deputies purchased from the Spotlight Capezio.

“That’s the only piece of physical evidence that ties her to the crime scene. And when I say ties, that’s through a series of inferences,” Rosenfeld said.

Despite the challenges, prosecutors were prepared to show that there was “a motive that any juror could understand” in Marlene Warren’s murder, Aronberg said.

“Who else would go to an isolated part of the county … and murder a woman who had no known enemies, without taking anything of value from the home, unless it was a crime of passion?” Aronberg said.

Scheduled to testify at trial was one of the employees of the Spotlight Capezio costume shop who was working the day a woman came in to buy a clown outfit and enough makeup to cover her whole face. Aronberg said she recognized Keen Warren as the woman who made the purchase.

A Publix employee also recalled a woman who resembled Keen Warren buying the balloons and flower arrangement found at Marlene Warren’s home, though Aronberg said it was an imperfect identification.

“You had a circumstantial case that, I think, would have had better success at the time it occurred back in 1990 than in the CSI-era of today, where jurors expect to see DNA evidence or video evidence or other types of direct evidence tying the suspect to the crime,” Aronberg said. “Here, we were undermined by the 33 years between the crime and the trial. We were undermined by Father Time.”

The decision about whether the human hair DNA would be admitted into evidence was one Suskauer would have made once the trial had begun, Aronberg said.

Defense Attorney Greg Rosenfeld included photos of opened evidence bags in a Feb. 18, 2023, motion, arguing fiber samples and other evidence should be excluded from Sheila Keen Warren’s trial because of possible contamination. (Court records)

Rosenfeld was prepared to argue that one of the hairs found in the LeBaron had both male and female DNA and that one in 25 U.S. Caucasians had the same DNA as the second hair, Rosenfeld said. He believes that once detectives heard of an affair, they honed in on Keen Warren as a suspect and “limited their investigation” with tunnel vision.

“They heard rumors that there was an affair, they said, ‘This is our suspect and we’re going to run with it,’ and they only focused on evidence that might suggest that she had some involvement,” Rosenfeld said.

Since taking the case, Rosenfeld said the discrepancy that has bothered him most was the fact that some of the witnesses to the murder said the clown was a man over 6 feet tall.

“It’s like having a puzzle and shoving puzzle pieces in that just don’t fit,” Rosenfeld said.

‘What would you do?’

Ahrens was in Las Vegas earlier this year when he got the call, asking if he’d approve of the plea deal. His grandmother, Marlene Warren’s mother, had just died. It took him days to decide.

“What would you do?” Ahrens said. “If she would have went to trial, she probably would have walked. I wasn’t going to take that chance …”

If his grandmother Shirley Twing would have lived to see the end of the case, she would have felt the same way he does, Ahrens said.

“It’s unsettling, but you have to settle with it, because it is what it is, and if you don’t, it’s only going to eat you up … That’s the reality of it,” he said.

Aronberg said “true justice” would have been Keen Warren spending the rest of her life in prison. But even if she had been convicted of first-degree murder, Keen Warren would have been eligible for parole after 25 years because of 1990 laws.

“We don’t live in the world of the ideal, we live in reality,” Aronberg said. “And the reality of a 33-year-old cold case means there has to be some give-and-take when your evidence starts to falter.”

Ahrens described his mother as an entrepreneur, a “ball of energy,” and an angelic woman who was quick to help anyone who needed it, even her tenants who may have been behind on rent at the properties she and Michael Warren owned. She loved art, was good at managing the family’s home life and gave advice to Ahrens. That’s something he still misses today, he said.

Ahrens’ brother, John Ahrens, died in a car crash a year-and-a-half before his mother’s murder. Ahrens said he recalled a shift in the family after his brother’s death.

“You could tell we were starting to get further away instead of pulling together,” he said. He noticed issues with his mother and his stepfather Michael Warren but thought it was simply “a phase.”

Ahrens said he was acquainted with Keen Warren before his mother’s murder and recalled one party at their Wellington home that Keen Warren attended. He didn’t learn until she was arrested in 2017 in Virginia that she had married Michael Warren.

Living in Virginia, Keen Warren went by “Debbie” and helped her husband run a popular restaurant in a nearby Tennessee town. No one knew of their past.

“She got what she wanted. She murdered the wife of the man she loved, and then she got to live the life that she had always wanted until dedicated law enforcement and prosecutors finally held her accountable,” Aronberg said.

The deal would not have happened without Ahrens’ approval, Aronberg said.

But a question many are left with: Is the killer clown case finally closed?

“If there is enough evidence that points to someone else, we would file charges,” Aronberg said. “But as of now, that doesn’t exist.”